How Kenyans embrace new changes through the 2010 New Constitution

FOR decades after independence in 1963, Kenyan politics evolved into a power structure centered on the presidency. Former presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi wielded powers that went beyond the normal scope of government.

FOR decades after independence in 1963, Kenyan politics evolved into a power structure centered on the presidency. Former presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi wielded powers that went beyond the normal scope of government, hiring and firing civil servants, dissolving parliament, controlling regional administrations, and even using security forces to suppress their opponents.

The “royal presidency,” as it came to be known, was the hallmark of Kenyan rule. Beginning in the 1990s, a movement for political change gained momentum. Civil society groups, churches, opposition politicians, and ordinary citizens demanded limits on the president’s power. The post-election violence of 2007/08, in which more than 1,000 people were killed and more than 600,000 were displaced, exposed the dangers of a “winner-takes-all” political system.

Following this, Kenya embarked on a historic reform journey that produced the 2010 Constitution, widely regarded as one of the most modern and effective constitutions in Africa. At the heart of the constitution was a deliberate effort to rein in the power of the president.

However, former vice-president Kalonzo Musyoka warns that Kenya is reverting to authoritarian rule, despite the safeguards set out in the 2010 Constitution. He says that, 15 years after the constitution was promulgated, the monarchy remains unchecked. Speaking at the annual conference of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) on August 15, Mr Kalonzo—who is also the Attorney General and an opposition politician—said that the Constitution’s promise to uphold the rule of law is at risk due to government repression, kidnapping, and human rights abuses.

“The years 2024–2025 have been a real example of government repression that has never been witnessed in Kenya’s 62-year history of independence,” Kalonzo said, citing cases of kidnapping, beatings of peaceful protesters, and criminal gangs operating under police protection.

According to him, youths exercising their right to protest are being abducted, tortured and charged under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Despite this persecution, they still believe that the Constitution is the bulwark against authoritarian rule. The Law Centre insists that the real strength of the 2010 Constitution in controlling the royal presidency is found in the Human Rights Chapter. “Based on Articles 19 and 20, the Human Rights Chapter is the heart of Kenya’s constitutional democracy.

These rights are not gifts from the government, but are the birthright of every Kenyan,” says a statement from the organisation. “It aims to protect human dignity, promote social rights, and empower individuals to fulfill their potential. By enclosing all government institutions, all laws, and even individuals, the Constitution places clear limits on how government power — including the presidency — should be exercised.”

Lawyer and politician Willis Otieno says the presidency has now “become a major threat to the Constitution.” “You are undermining and mocking the institutions created by the Constitution. Look at the recent efforts to interfere with the powers of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC), or the appointment of presidential advisors when the cabinet is the only one with such powers.” Professor Gitile Naituli of Multimedia University says the 2010 Constitution was specifically designed to dismantle the authoritarian presidency, by decentralizing power to more powerful institutions.

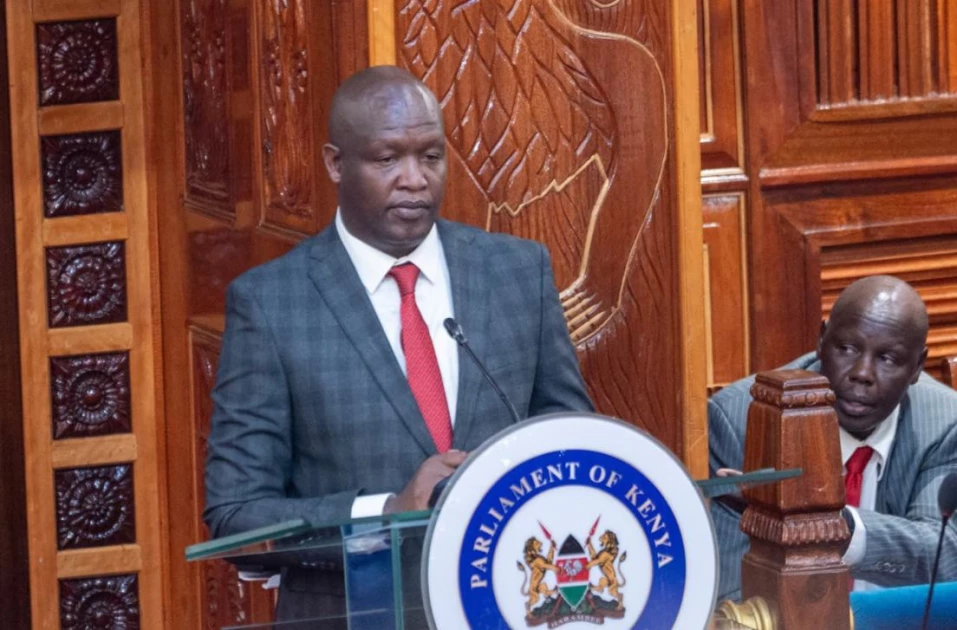

“By establishing an independent commission, a bicameral parliament, devolution, and placing specific limits on the president’s powers, the drafters of the Constitution attempted to correct decades of authoritarian rule.” According to Prof Naituli, the changes have been largely successful. “Unlike previous eras, current presidents do not have the same supreme power as their predecessors. An independent judiciary, devolutionary structures, and a relatively independent parliament have created alternative centers of power.”

However, he warns that the gains are not complete: “Although the Constitution limited the powers of the presidency in writing, its implementation has not lived up to its intent. “Checks and balances can still be politically hijacked, with networks of corruption reviving the presidency to become more powerful than the Constitution intended.”

-og_image.webp)